Pagan-Christian not Judeo-Christian – Part 2

Uncovering the pagan foundations of Christian doctrine.

An important difference between the Greek mysteries and Christianity is that, according to Christian theology, man’s destiny after death is determined by his conduct, since baptism (i.e. initiation) does not, by itself, guarantee salvation. As Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430) explains in The City of God, souls are judged upon reaching the otherworld and divided into four groups: the truly virtuous, such as saints and martyrs, are sent to Heaven, while the irredeemably evil are damned to eternal punishment in Hell; those who are mostly good or mostly evil, on the other hand, await the Last Judgment while purifying themselves in Purgatory or in a slightly less bad region of Hell, respectively. If we read Plato’s description of the afterlife in the Phaedo and in the myth of Er at the end of the Republic, we will find that it resembles Augustine’s model almost to a t – which is hardly surprising, considering that Augustine came to Christianity through Neoplatonism.

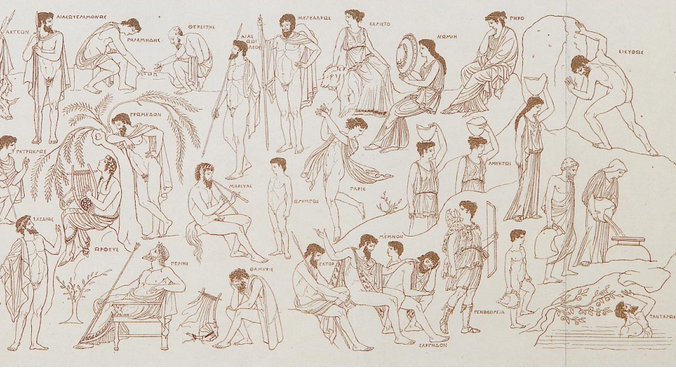

Plato, for his part, drew heavily upon the Orphic mysteries in creating his own eschatological system, which incorporated both the idea of judgment and retribution and the doctrine of reincarnation. Upon reaching the otherworld, the dead – or rather, their souls – are examined by the infernal judges and sent to the appropriate destination: up to Heaven if they are virtuous, down into the depths of Tartarus if they are wicked. While the truly virtuous – that is, according to Plato, the philosophers – and the incurable sinners – such as tyrants and especially violent criminals – spend all eternity in their otherworldly destinations, the rest are bound to come back to earth after a period of a thousand years from the time of their birth: those who have led a virtuous life but have not duly purified themselves – through the pursuit of philosophy – await the time of their next incarnation in a lower region of Heaven, whereas the curable sinners serve their sentence in the appropriate region of Tartarus; the majority of souls, neither particularly evil or virtuous, reside in a purgatory-like place, the Acherusian swamp – a clear reference to the mud-lying uninitiated of the Orphic tradition. It is easy to see why the doctrine of reincarnation was left out by early Christian theologians, as the idea of having multiple chances at life somewhat lessens the appeal of a salvation cult, at least for the average person – and, indeed, the initiates of the Orphic-Bacchic and Eleusinian mysteries believed that they were destined to escape the cycle of reincarnations and live forever free of toil in the Abode of the Blessed.

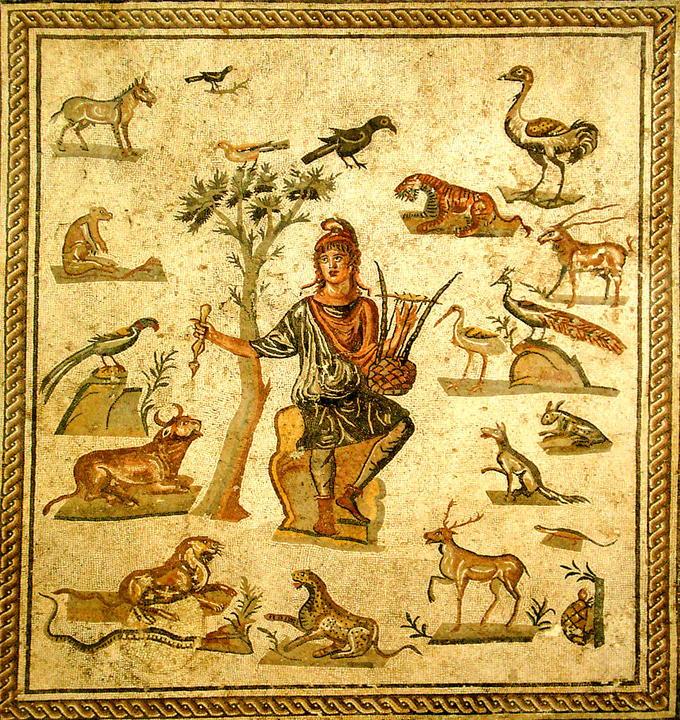

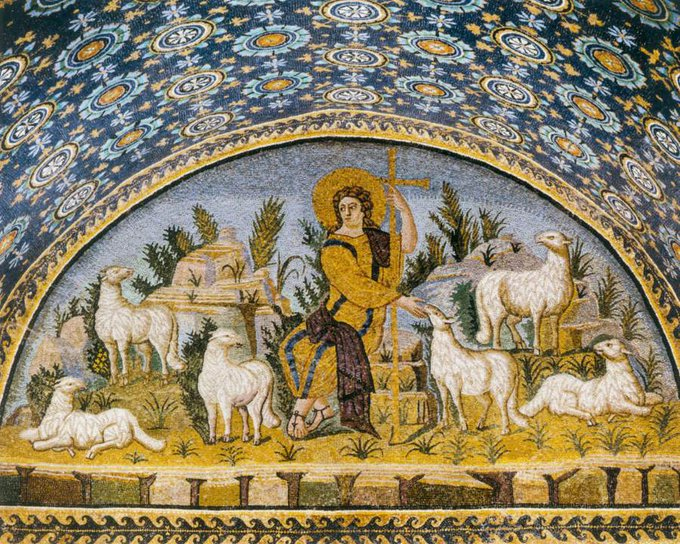

There are many other clues which point to the influence of ancient mystery religions – and especially of the Orphic-Bacchic mysteries – on early Christianity. The Greek term mysterion, used in the plural to denote secret initiation rites, is frequently used in the New Testament and was adopted by the early Church to refer to the sacraments. The figure of Christ is itself largely – though not exclusively – modeled on Dionysus: the two both share the same fate of a violent death and subsequent resurrection and they are both closely associated with the vine, to the point that wine is seen as a symbol of their blood8. Christ is not, however, a purely Dionysian figure: for instance, his healing miracles recorded in the Synoptic Gospels are reminiscent of the miracles attributed to Asclepius, the Greek god of healing and medicine, son of Apollo and a mortal woman; early depictions of Christ as Orpheus charming the animals confirm his connection with Apollo, who was sometimes considered as Orpheus’s father and was also described as charming animals with his music. Other depictions show Christ as Sol Invictus (Unconquered Sun) and, indeed, December 25th, which was celebrated as the dies natalis (birthday) of the Roman sun god – officially since 274 AD – became identified with Christ’s birthday by the time of Augustine (late 4th century). Besides, it is no coincidence that the Christian day of worship is not Saturday – or Saturn’s Day (dies Saturni) as the Romans called it – but Sunday (dies Solis), officially declared the Roman day of rest by the emperor Constantine in 321 AD9.

For the sake of brevity, I will not discuss the adoption of pagan festivals and traditions by the Christian church as the new official religion of the power-holders spread within (and eventually beyond) the borders of the Roman Empire – which on its own could be the subject of another article. Suffice it to say that what originally started as an offshoot of Judaism underwent a radical transformation by incorporating elements from Greek religious thought and Greco-Roman religion – especially mystery religions, such as Orphism and, to a lesser extent, Mithraism – and, later on, Celtic and Germanic tradition, so that modern Christianity hardly resembles the apostolic faith. Over the centuries, this realization has prompted many religious reformers to strive to return to a primitive form of Christianity, but I argue that a much more healthy and fertile approach would be to embrace the contribution of ancient philosophy and pagan religious tradition as foundational to Christianity. Indeed, what would the Christian faith be without the influence of Greco-Roman and Germanic culture if not another form of Messianic Judaism? Even the Hebrew faith itself owes much to Greek and Hellenistic thought: for instance, early Judaism was polytheistic – as the Old Testament attests – and the belief in a single creator god can likely be attributed to Plato’s influence on Hellenistic Judaism10. Let us then proudly reclaim Christianity as an authentic expression of our ancestral Spirit – not in contrast but rather in continuity with earlier forms of spirituality practiced by our more distant ancestors – and let us also rediscover and reconnect with our pre-Christian roots. As Plato would say, let us learn to remember what we have forgotten.

8. Dionysus’s close association with wine is attested as early as the writings of Plato and the Orphic Gold Tablets. The Greek geographer Pausanias (c. 110 – c. 180) relates a miraculous occurrence on the island of Andros, where at the time of the festival of Dionysus wine flowed from the temple of the god (VI 26.2). In the Greek novel Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius (2nd century AD) Dionysus is said to have turned water into wine, just like Jesus in the story of the marriage at Cana (cf. John 2:1-11); elsewhere in John’s Gospel (15:1-17) Jesus declares himself to be the “true vine”.

9. The Council of Laodicea (363) officially outlawed the observance of the Jewish Sabbath.

10. See especially the creation myth in Plato’s Timaeus.

Become a Patron!

Well written and interesting connections, but what is missing is a compelling interaction with 500 years of critique made by Reformed and Evangelical scholars. Academics who pointed out these very connections half a millennia ago are so numerous that to not engage them is to ignore centuries of insight and true Christian movement. Interaction with figures such as John Calvin, Martain Luther and John Knox to name just a few would surely add to the discussion, no? There is a seed of truth here, but the very existence of the Protestant denominations is proof positive that the break away from the Roman Catholic faith (Pegan mythology) and restoration of the Apostolic faith was a historic attempt to remedy the Constantinian-like syncretistic error. The New Testament redefines everything. Just because there is an overlap between ancient near-eastern belief systems and Judeo-Christian dogma does not lead to the conclusion that the former must facilitate the latter.

Why can’t Protestants spell ‘pagan’ correctly? Or are you the same person who wrote to me on twitter? Anyhow, thank you for your feedback. As you might be able to tell from my article, my focus is not on Christian theology per se, but on its connections with pre-Christian thought and religion. My aim is diametrically opposed to that of Protestant scholars, such as A.H. Lewis, who seek to ‘purge’ Christianity from all of its pagan components. I want to encourage Christians to research and embrace their pre-Christian heritage. If you want to follow the more radical Protestant churches and practice a sort of Messianic Judaism instead (because that’s what you’re left with, once you remove all pagan influences), you are welcome to do so. This, however, is not Christianity. Let’s just be honest about that.

Amen

I find this to be a life giving, mind opening turnof thought.

As for the Protestant rebellion, lead as it was by gross materialists and pitiful folk like Cromwell, Henry VIII, Luther, Calvin, degenerates, their level of thought leads to a dry land and a salvation cult of false promises.

Resurrect the true and higher aspects of paganism, Christ I AM utterly, and give people a spiritual life again.

This will help make both Christianity and paganism great again.

Great, breakthrough article.

This framing will help make both Christianity and paganism great again.

Thank you very much, Mmc. I really appreciate your comments.

Great article, I think it will help many cross the divide that has been cast between Christianity and European heritage.