Art School: The Great Enemy of Aesthetic Tradition

By Alice Crawford McKinty

The trope of the talentless, directionless art graduate has loomed large in the public imagination for many years now. The repetitive abstract garbage produced by students supposedly receiving a top-tier education among respected scholars, historians and practitioners of their field may leave many of us baffled, but today’s students aren’t entirely to blame.

With the advent of Modernism c. 1910, artists in the West famously rejected the rich aesthetic tradition which preceded them. The anatomical perfection of the human form, the magnetic realism unlocked by perspective, the study of light and colour, and most significantly the unbounded reverence of beauty in landscape, still life, architecture, religion, history, mythology, and so on – wisdom developed over the course of millennia – were cast aside in favour of absolute creative freedom. Modernist philosophy insisted that technical constraints weren’t necessary, and that anything could be art if we only opened our minds to viewing it as such – but though this might seem an enchanting notion, it is in fact nothing more than the abolishment of artistic standards. If anything can be art, then nothing is art – yet when we compare Duchamp’s urinal to Michelangelo’s David; Botticelli’s Birth of Venus to Picasso’s broken, disfigured portraits, it is clear to all which works are most deserving of the title.

Beautiful artworks have a clear value that no Modernist creation can match, and as a traditional painter and recent graduate of a Fine Art Masters Degree, I hope to highlight the difficulties faced by students who speak out against Modernism in today’s University environment, to shed light on the inner workings of these institutions, and to provide some clarity on the wider issues Modernism poses to our culture. Whilst very keen to market themselves as such, Art Schools today are not places in which students are free to follow their creative impulses – the Modernist approach is the only one permitted, and indeed the only one taught. For the vast majority of students, technical drawing and painting lessons aren’t available – most Universities simply provide life models for an hour or two each week, leaving those who attend without a modicum of useful instruction or guidance.

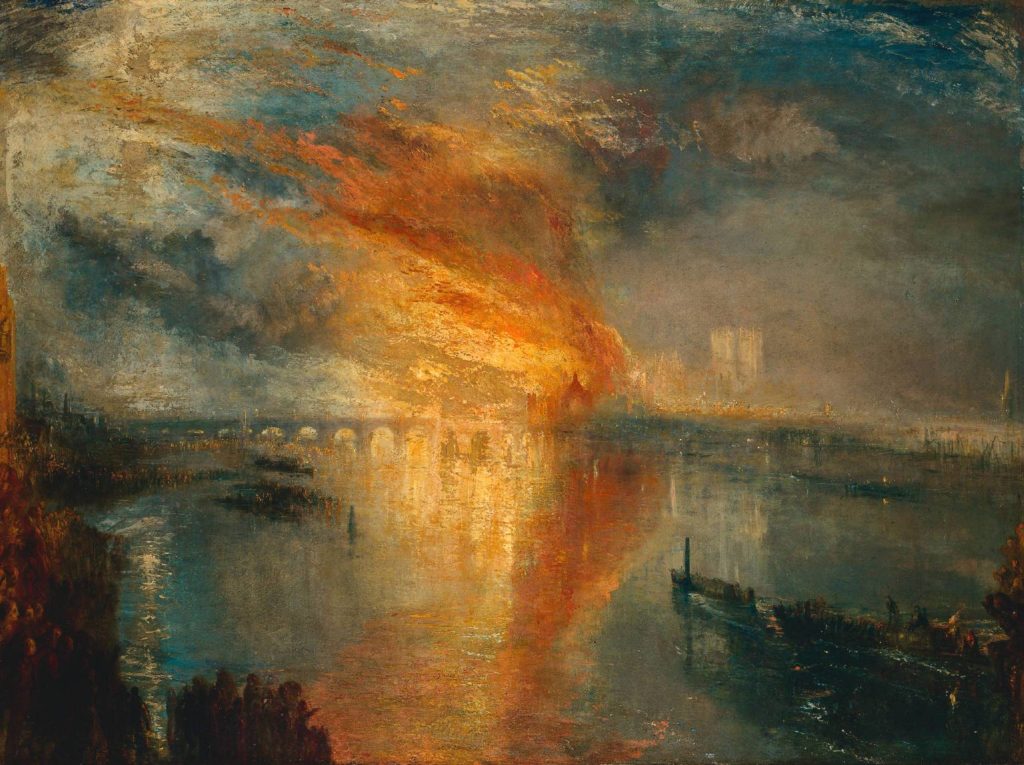

With twice-weekly art classes on perspective, anatomy, and still life, my 65 year old father received more instruction in drawing during his first year of high school than I gained from four years of higher education. Studio spaces are awash with scribbles, splatter-paintings, defiled mannequins, and junkyard scrap; corridors echo with endless babble about what it all ‘means’; and tutors are not infrequently heard proclaiming that every painting by Turner or Constable should be burned.

A particular teacher of mine was even gracious enough to share a video of his ‘performance art’ with the class – in which he stood naked on stage, masturbating, ejecting frankfurters from his behind, and shouting profanities into a megaphone.

For anyone who loves art in its traditional, beautiful form, and goes to university with a heartfelt desire to learn, the atmosphere in these environments is sickening. I witnessed numerous students with far more talent than myself brought to tears by tutors’ vicious criticism of their delicate portraits and vivid comic-style illustrations – their spirits slowly crushed, most eventually conceded to lower the standard of their work. Though it may seem dramatic, this is the reality of Modernist art teaching – when one creation can no longer be judged ‘better’ than another, the lowest common denominator soon reign supreme.

What is more crucial to understand, however, is the damage that such aesthetic barbarism wreaks on the surrounding culture. Beauty was once not only an artistic ideal, but a value to strive toward in all facets of life. Philosophers such as Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant included in their Aesthetic tomes everything from fashion, to architecture, to interpersonal manners; firmly believing that beauty of the outer form was reflective of beauty within. Indeed, the very realism that Modernism left behind suggests a certain objectivity of mind which, though it may be manipulated by the artist in any way they choose, nonetheless remains familiar and transparent enough for the viewer to assert moral judgement. Abstract art, objets trouve, installations, etc. strip the viewer of this foundation. We cannot know the artist, nor his vision of the world, since nothing by his hand leaves itself open for us to recognise and understand. Just as the Islamic veil covers the face of its wearer, shielding her from external judgement upon and appreciation of her beauty; so Modernism covers the spirit of the artist, and shields him likewise. As a voluntary act, we might consider this one of deception or cowardice; but as imposed rule, as it is in our Universities today, it is nothing less than the outright oppression of beauty, virtue and individual creative freedom. With beauty suppressed, only ugliness can remain – and whilst we might forgive the hideous tower blocks and foul-mouthed, tracksuit-clad youths of our time, the degradation of art is of far greater concern.

True art provides a spiritual refuge – a purpose which has remained unchanged since Da Vinci and Michelangelo lovingly adorned the walls of churches and cathedrals, aiding men and women in their communion with God. And where Modernist galleries lie empty but for a few quirky stragglers, traditional galleries bustle with life day after day. Since the Modernist notion of freedom is not openly accompanied by beauty; it is represents only the freedom to remain neutral, or to inject ugliness and negativity into our world. There are, of course, innumerable cases to be made in favour of those abstract works which through simple harmony of colour or rhythm of line prove pleasing to our senses – but if we are to restore the world of art to its natural order, these must be put in their rightful place. Even the most agreeable examples of Modernism, such as Kandinsky’s works of the late ’20s, are in truth ‘low art’ – requiring minimal skill, minimal knowledge, and minimal creative thought to execute to a reasonable standard; whilst the very worst, such as Tracey Emin’s ‘My Bed’, are nothing more than public displays of poor taste and depravity. In allowing the Modernist lie of free-flowing creative genius to seep into our educational facilities, we have robbed today’s youngsters of the opportunity to create work of real value. Rather than receiving a rigorous education in the skills necessary to conjure beauty and to excite wonder, they are left to fend for themselves in an environment where the inmates run the asylum, and reward can only be gained through regression. But those seeking an accessible entry-point to the spiritual balm of beauty need only dare to look back in time.

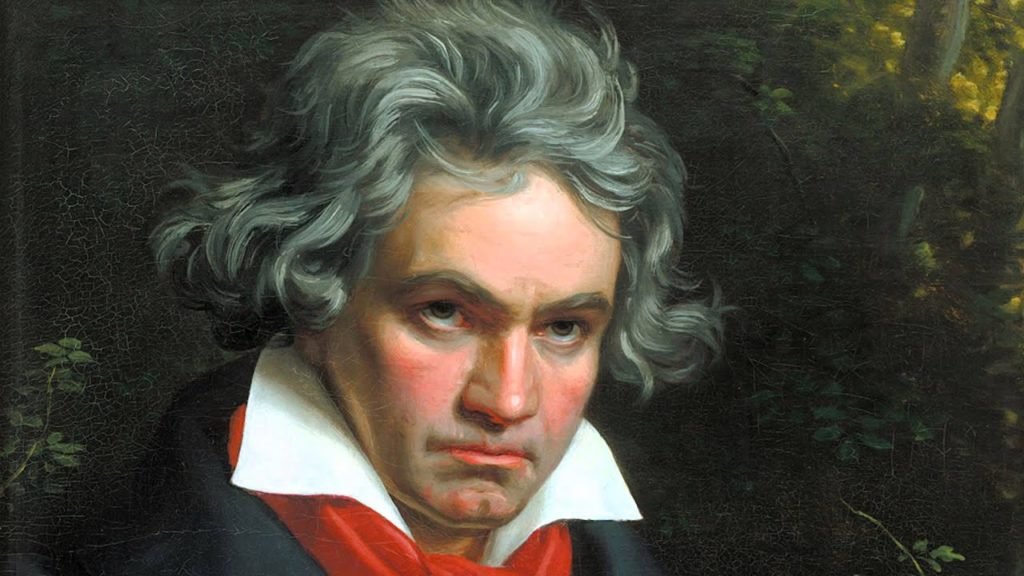

In my own case, the realisation of beauty’s value was not gained through art at all, but rather through music. By the chance meeting of a Classical pianist specialising in the work of Beethoven, I learned that no matter what my tutors may claim, true art is not for the purpose of shallow amusement, grandstanding or gimmick – it communicates from the very depth of the artist’s soul, and provides a place in which we can appreciate the innumerable delights and struggles of being human. Though it may seem a little romantic, it is the very love of life itself which lies at the core of most every great work of art in the Western tradition – and which has driven centuries of artists to offer every ounce of their dedication, skill and wisdom to the task:

‘Just as man sees woman and, as it were, makes her a present of everything excellent, so the sensuality of the artist puts into one object everything else that he honours and esteems’ – Friedrich Nietzsche [Will to Power, p. 424-425]

With this in mind, it is perhaps no surprise that in our world of broken homes, dating apps, endless streams of digital information and minimal time outdoors, so many of us today lack the presence of mind to fully appreciate art. Just prior to the outbreak of Modernism, however, lies a somewhat overlooked sweet-spot for anyone wishing to learn. The simple charm of Impressionism not only functions as a wonderful foundation for young artists, upon which ever-greater technical precision and creative imagination can be built; but also provides something of a lesson in artistic morality – encouraging us to look outward, and consider beauty objectively using a lens through which, as Claude Monet remarked, ‘It is not necessary to understand, it is simply necessary to love.’ If we are to retain any semblance of the good in art, we must accept that Modernist regression dishonours the fundamental principle of love – a force which strives forever upward in an effort to become worthy – and rebuild our aesthetic tradition from the ground up, leaving our damaged Art School institutions behind.