No Future Without A Past

Nemo

Futurism was a joke of a movement and the thing that did for it was its attempted rejection of all previous artistic tradition and, as Italians, their own heritage as the heirs of Roman civilisation and the Renaissance. I suppose such baggage was problematic as they aspired to signal cutting-edge modernity, or they simply felt the weight of such a history too pressing, the bar it set too high.

These factors meant Futurism could never find a form to express Marinetti’s manifesto, in which the quasi-religious talk of a world of dynamic forces facilitated by technology was problematic in itself.

The painting produced by the Futurist group was often simplistic and childlike – Giacomo Balla’s 1910 painting of a street lamp and 1912 picture of a dog walking both featuring the kind of motion lines an infant would use. Having proved they lacked the nous and talent to create a visual language to express their ideas, they looked to appropriate one.

This led them to Cubism in Paris, an art that ticked their box of appearing cutting-edge. They began copying Cubist works, in painting and collage, but the problem was they were copying minor artists who themselves misunderstood “Cubism”.

True Cubism was essentially the art produced by Braque and Picasso from 1907 to 1914, essentially an anti-aesthetic game in which they undercut all previous artistic traditions. Their works were interrogations of how three dimensions can be represented in two, creating continuities of structure rather than continuities of space, always emphasising the planar surface and the artifice of the image. In this sense, true Cubism suited the Futurists as it was giving a middle finger to everything that had gone before.

But it was not exhibited or widely seen. Viewing was mostly restricted to a small group of intimates including artists like Gleizes, Leger and Metzinger. What the world saw and knew as Cubism was their imitation of the output Braque and Picasso – and they clearly did not understand what they had seen, simply producing crude sculptural forms in three-dimensional space. Leger even developed a style dubbed Tubism, using more rounded, tubular forms as his signature flourish (or gimmick), setting him apart from the “cubes” of the others.

So, while the foul and destructive output of Braque and Picasso was in itself a coherent representational language, the Futurists appropriated a “Cubism” that was a misunderstanding and misrepresentation of it – guaranteeing that their output would be garbage.

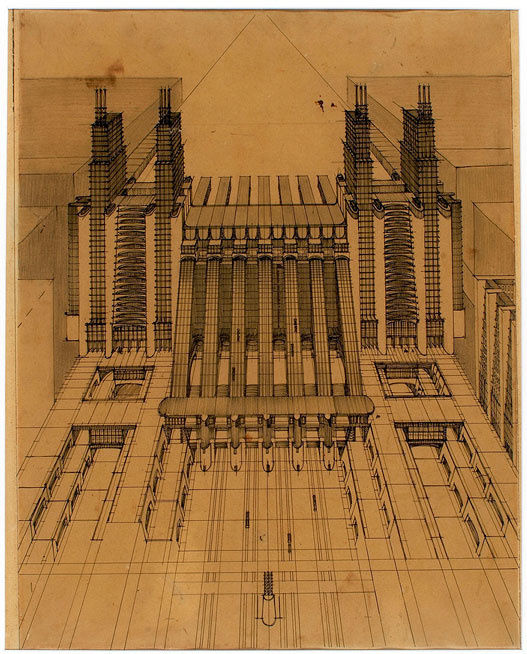

But perhaps the best example of the problem with Futurism was its architectural output – or utter lack of. Antonio Sant Elia started out doing Art Nouveau-style designs, operating in the last true organically evolved European artistic tradition.

Aligning with Futurism, he drew inspiration solely from modern industrial design (including factories, power stations and grain silos) and materials (chiefly pre-stressed concrete).

His designs look spectacular and were an inspiration for the cityscape in Blade Runner. But they simply fetishise and reference industrial models that signify the modernism he strove for, while his forms have no consideration for function.

Only one building designed by Sant Elia, a small pre-Futurist project early in his career, was built. The scale of architectural endeavour meant the bulk of his work, his ideas, never found material expression – whereas his fellow group members were free to churn out lots of bad painting.

Futurism was a ridiculous movement but at least it has value as a warning to those who would seek to malign or cast off tradition.