Plato, the politician?

Most everyone has heard about Plato the philosopher, pupil of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle; many are even familiar with Plato the writer and the myth maker, creator of the famous Allegory of the Cave, but very few people know about Plato’s disastrous involvement in real-world politics. Coming from an aristocratic family, whose lineage could be traced back to the famous lawmaker Solon on the maternal side and to the last king of Athens on the paternal side, the young Plato would have been destined to a brilliant political career, if it were not for the adverse circumstances surrounding his early life.

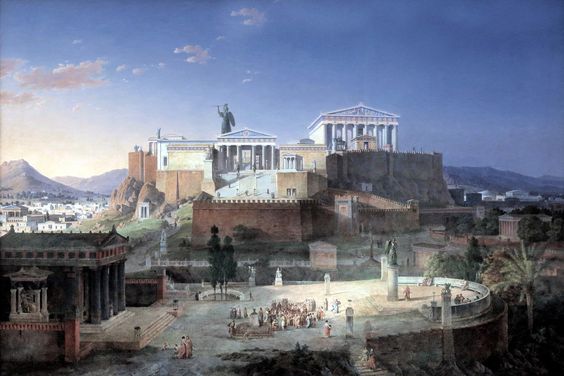

The tragedy of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), in fact, precipitated Athens, once the most powerful and prosperous city in Greece, into a state of political and economical decay from which it would never fully recover. Moreover, Plato’s connection with the so-called Thirty Tyrants (the pro-Spartan oligarchs who held power in Athens between 404 and 403 BC), whose leader Critias was Plato’s great-uncle on his mother’s side, de facto prevented the future philosopher from actively participating in the newly reinstated democracy. Thus, when the radical democratic government condemned Socrates to death – officially for not honoring the gods of the City and introducing new deities, but his anti-democratic views and his ties to the enemies of the Athenian democracy (several of the Thirty, including Critias, had been students of Socrates) were likely the real motivation –, Plato decided to leave his city and traveled extensively throughout Greece, Southern Italy and Egypt.

While in Italy, Plato visited the court of Dionysius I in Syracuse (Sicily), where he befriended the tyrant’s brother-in-law, Dion. While Dion became a fervent supporter of Plato’s ideas, Dionysius did not appreciate his exhortations to pursue philosophy and virtue, which he perceived as offensive, and became so enraged at the Athenian, that he wanted to put him to death. Thanks to Dion’s intervention, however, Plato was instead sold into slavery and, having been bought – and later freed – by a friend of his, who recognized him at a slave market, he was eventually able to return to Athens.

Two decades later, after the death of Dionysius I, Dion convinced Plato, then about sixty, to come back to Syracuse to become the teacher of the young Dionysius II, whom he believed to be a viable candidate to realize Plato’s ideal of the philosopher-king. Plato’s efforts, however, were undermined by Dion’s political enemies, who accused both of conspiring against the tyrant; as a result, Dion was banned from Sicily four months after Plato’s arrival. On the other hand, Plato, for whom Dionysius developed a jealous affection, ended up being held against his will in Syracuse; eventually Dionysius agreed to let the philosopher leave, with the promise that he would return at a later time. Shortly afterwards, Plato was joined by Dion at the Academy – which he had founded upon returning to Athens from his first journey to Sicily.

Seven years later, under strong pressure from both Dionysius and Dion, Plato agreed to travel to Syracuse once again. This third and last visit put a definitive end to Plato’s political adventure: caught up in the power struggle between Dionysius and Dion, the philosopher was suspected by the tyrant of plotting to overthrow him and only through the intervention of mutual friends was he able to escape Sicily and return safely to Athens. Dion, however, was not as fortunate and died in the attempt to overthrow Dionysius.

So, what can we learn from Plato’s failure? Essentially, that Virtue cannot be taught. One can only become what he was born to be and very few people are born to live a life of abnegation in the pursuit of Virtue – this is, indeed, the life of a philosopher according to Plato. Only such a person – someone whom we might call a saint – would be able to bear all the responsibilities of an absolute ruler without being corrupted by power. The goal of education, then, must be to select the viable prospects and guide them in developing their innate talents to their full potential: in short, the opposite of what the modern education system is designed to do. I, for one, suggest we learn from Plato and start cultivating a new generation of leaders that will be actually worthy of the name.

Become a Patron!