Christmas: Saturn and Solstice

The period of feasting and merrymaking surrounding the winter solstice (Christmas) is an ancestral practice of truly archaic origins, with durable attributes more antiquated than commonly realized.

This is despite the fact we still instinctively venerate them, as even atheists can not give up the practice of Christmas. The strange and mirthful elements of this holiday are old enough to span several religions, over many centuries, with remarkably similar resurgent qualities. This date on the calendar has been important to our ancestors for perhaps longer than is apparent, and the event itself is somewhat proportionately larger and more inexplicably powerful than even the specific deity or theurgy it is purporting to celebrate. That is, this date, and many of the interesting specifics of its celebration from stockings to carolling, may go back to the conquering horsemen who founded the original kingdoms of Europe, back into cosmological oral tradition, and back even further than that. It’s slightly bizarre and recurring themes speak to a spiritual impulse, or hereditary memory, that re-emerges regardless of historical shifts in cultural or moral conduct.

The artifacts of this festival as still practiced today are the habits of a continuous ever-reborn genealogical animal.

We understand enough history now to know the solstice was very important to the ancient Neolithic people of Europe of which we know so little. Monuments such as Newgrange in County Meath, Ireland (3300 BC ) were constructed so that the holy sunlight strikes the interior of the mound perfectly timed on the day of solstice. It seems to have been an event of extreme importance to what we assume were an oral tradition people. The more recent historical incarnation of this of which we know the most is the Roman holiday of Saturnalia. This itself descends from its Greek incarnation as Kronia (Kronos being the Hellenic precursor to Saturn). This in turn has similarities to the Norse festival of Yule, and the Celtic Meá Geimhridh or Alban Arthuan, all of which would likely have evolved from a shared distant origin celebration.

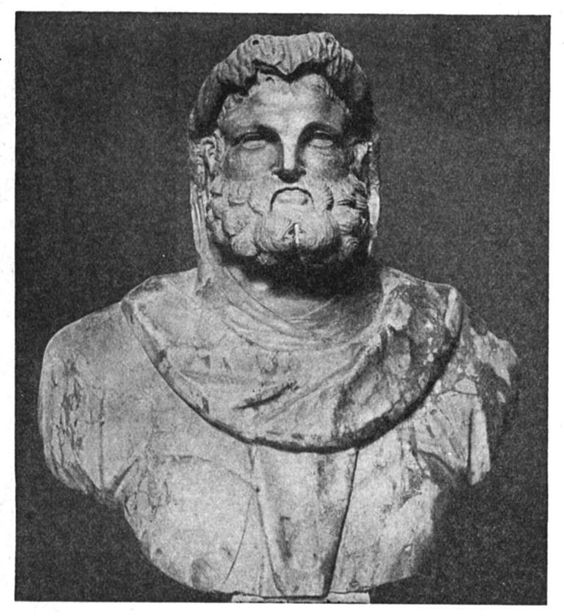

The name Saturn derives from Satus which means sowing. It is believed that it has origins involving a farmer’s holiday marking the finale of the autumn planting season. How it migrated to the time of the winter solstice is uncertain. Saturn himself is a titan, father of Zeus (Amon-Dias, Deus, Jupiter) and is portrayed as an agricultural deity carrying a sickle. He is associated with time, liberty, wealth, as well as being a harvest god. Within this father-god are joyful and utopian aspects of careless well-being (Christmas cheer), which can at other times reside side by side with threatening elements of danger.

According to ancient legend Saturn long ago brought about a golden age upon the earth, when he came down among us with his sickle. He imparted to us an agricultural knowledge, and humans enjoyed an innocent time of spontaneous bounty with the wisdom he bestowed. A sort of ‘garden of Eden’ age. The merry revelries of Saturnalia were intended to reflect this idealized condition of life from this once-dreamed lost age.

One of the first and most crucial factors of this celebration, true of each of its incarnations, is the date. The exact days may vary or change slightly, but our instinct appears to insist that we feast and carouse around the time of the winter solstice. The shortest day of the year, which is the dying time of the old year, as a new year is born. The original date of Saturnalia was December 17th and this was eventually expanded by Emperor Domitian to culminate on december 25th, again based around this winter solstice schedule. During the Imperial period there was an attempt to shrink the holiday to three days, with only limited and temporary success. The party could not be defeated. This failure is our first example of how the attributes of Christmas are instinctual, or comprise an inherited memory that triumphs over all attempts to alter or extinguish it. Some of these festive attributes are strange, when viewed objectively, and seemingly among them (quite hilariously) is the tradition that the party must continue for a period of roughly a week.

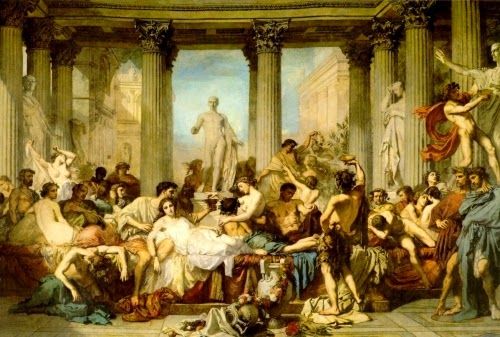

The Saturnalia festivities began at the temple to Saturn on the Capitoline Hill (known in earlier times as Mons Saturnius). A crowd would congregate upon the summit about the statue of Saturn which stood outside the temple, which for most of the year had distinctive wool wrappings tied about its feet. Unusually, this could be the hallmark of the tradition we carry on in the form of Christmas stockings. The holiday officially began when these wool wrappings were unravelled from the feet by the priests. The statue itself was hollow and (fascinatingly) filled with olive oil. After this stocking removal, a sacrifice was performed before the crowd, then the great public feasts began, with heavy drinking, and mock gladiatorial games were performed by women and dwarves (again celebrating role reversal and a temporary relaxation of civic norms). Following this the crowd returned to their homes to a private banquet, followed by gift-giving, continual amusements, and more reversal of Roman social norms as the class system was temporarily suspended.

Every citizen wore the cap of freed slaves, called a pileus, which was a brimless conical hat usually made of leather or felt, occasionally with a horsehair crest. A Christmas party hat, if you will, not impossibly distant from the hat worn by Santa’s elves.

Their journey to their homes were accompanied by loud singing and cries of ‘Io Saturnalia’ ( the Io is pronounced something like ‘eeyo’ or just ‘yo’). Their experience would have been familiar to us: streets lit up with candles and trees decorated with solstice icons (where they stood, not indoors). The festive period was categorized as a legal holiday referred to as a dies festus, when no public business could be conducted. As well as the pileus, everyone dressed in simple tunics, including senators and magistrates and people who normally portrayed status in their dress. Sometimes for the dinner feast colourful garments normally considered in poor taste were donned (Christmas jumpers).

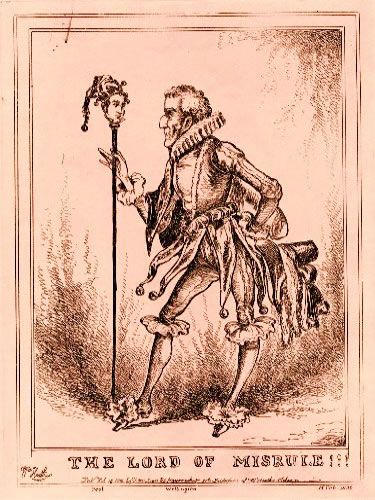

Once at home from the temple ritual and public feast, the party continued. A person was selected within family households by rolling gambling dice (a normally restricted activity) to randomly select the Saturnalian monarch: the Saturnalicius princeps (“Ruler of the Saturnalia”). In the spirit of the season this person was often arranged to be a child or slave, and the commands he or she gave were obeyed without question, and has been compared to the medieval custom of the Lord of Misrule at the Feast of Fools. The princeps commands were related to revelry, typically: “Remove your clothes!”, ‘‘Dance!’’ or “Dip your head in the water bucket!” The wealthy were expected to show charity and pay the month’s rent for those they knew living in poverty. Sometimes masters and slaves had to swap clothes. The masters had to serve dinner to the slaves.

This home-based celebration of Saturnalia could be performed outside Rome, anywhere in the Empire, and was. Schools and courts were closed, and no declaration of war could be made. Again the aspect is familiar to us, as we too know this season as a time of truce, a temporary abolition of all hostilities in the name of goodwill.

The poet Lucian of Samosata (AD 120-180) said of Saturnalia:

‘During my week the serious is barred: no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games of dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping … an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water – such are the functions over which I preside.’

This sounds fairly Dickensian.

Normally strict gambling restrictions were lifted and slaves and the poor were allowed to gamble with nuts. In the spirit of the season a willing rich man might gamble real money against his own slaves who wagered only nuts. Outrageous turns of fortune were likely. Again our modern holiday has as certain mild synchronicity for the consumption of nuts.

Similarly to today, the exchanging of gifts was very important, and not just between family, but between everyone you knew, and even some you didn’t. The most popular gift was called a sigurnalia, which was a wax or clay doll – accompanied by a note or poem; essentially Christmas cards. Gifts could be as varied as writing tablets, combs, sausages, axes, clothing, live birds, cups, or a more costly slave or exotic animal.

Revellers in the streets sang and knocked on doors like carollers or wassailers. If the door was answered a gift was expected. Everywhere was lit up with candles, symbolizing the quest for knowledge and truth. We do the same today, instinctively, with Christmas lights.

We obey the ancestral urge, not knowing nor caring its specific source. As did they.

In the later empire the renewal of light and the coming of the new year was celebrated in the post-Saturnalian holiday of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the “Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun”.

The traditions of Saturnalia have many living parallels in medieval customs and their ghosts in our contemporary culture, all of which circle spectrally about the significance of the winter solstice. A significance which is perhaps cosmological, which has now become distant to us in the age of nighttime light pollution and busy modern distractions. The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast or heavily influenced the new seasonal celebrations of Christmas and the New Year.

However Saturnalia’s initial religious conversion was not Christian, but the aforementioned festival of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti. Emperor Aurelian introduced this holiday in 274 AD, making this cult of Sol Invictus the state religion, and keeping December 25th as the official day of Dies Natalis. Sun worship brought the holiday back closer to its Neolithic cosmological origins. The Sol Invictus religion was also part of the popular cult of Mithras, itself containing many strange parallels with the worship of Jesus, with which it was engaged in rivalry for predominant imperial religion.

But despite efforts by later emperors to control the uncontrollable spirit of Saturnalia, the Sol Invicta festivities ended up looking very much like the old Saturnalia.

Once again the party won through attempts to alter it.

Sol invicta’s brief period of cult success lay in its ability to assimilate previous beliefs, it was however a pseudo-monotheistic cult, or at least heading in that direction, and helped pave the way for the Christianity which followed. This came about partially due to the first Christian emperor Constantine being brought up in a Rome dominated by the Sol Invicta cult, which had eased in these pseudo-monothesistic elements already. The popularity of the Dies Natalis festival (largely indiscernable from Saturnalia) continued into the 4th century AD, and as the Roman Empire transformed to a Christian one, the ancestral customs reshaped themselves about the celebration of Christmas. Eventually the last remaining reference to Saturn survived only in the New Years depiction of Father time with his sickle. It might be speculated father Christmas had a similar origin, though often it is speculated that he has a basis in Silenus or Odin.

When Constantine converted, Christianity did not become the Roman Empire’s official religion overnight. Saturnalia continued to be celebrated over the following century. Essentially, again, the party couldn’t be stopped. Our earliest known reference to Christianity commemorating the birth of Christ on December 25th is the Roman Philocalian calendar of AD 354. But there are other accounts that Saturnalia was still practiced as of old, such as the 449 AD Christian calendar of Polemius Silvus which states that celebrations were occurring which ‘used to honour the god Saturn’. Suggesting it had by that time become a kind of arcane irreligious jubilee. Though subdued, the period of merrymaking was being observed.

The holiday of the winter solstice as we celebrate it today (as Christmas) has conglomerated customs not from a direct distant lineage but from parallel cultures which bifurcated from an original long-forgotten seasonal party. From what is known of the ancient Celtic religion, for instance, we get traditions involving certain plants. Druids would cut the mistletoe that grew on the oak tree (not to kiss each other as far as we know) to offer as a blessing each year. They continued to venerate the Neolithic monuments (Newgrange in Éire, Maes Howe in Orkney, Scotland and Bryn Celli Ddu in Ynys Môn) which were the burial chambers of an elder race which captured the full impact of the suns rays during the solstices.

The Druids celebrated the festival of Alban Arthuan (also known as Yule) at this time, they too burnt a Yule log and decorated trees, and venerated at this time plants such as Holly and Ivy. According to their myths, on the solstices of each year the Oak King (the light) and the Holly King (the dark) would be engaged in battle, with the Oak King emerging victorious at the winter solstice, enabling the return of the light. This tradition still lives today, certainly with the prominent use of holly and the of bringing wreaths and green things into the home.

The Germanic version of Saturnalia was of course Yule or Yuletide, which is a festival which also later underwent Christianised reformulation, resulting in the term Christmastide. Many present-day Christmas customs stem from this tradition, itself stemming back almost 7000 years. Some of these are: wassailing (caroling), the yule log, greenery in the household, gifts and celebration of the ‘Yulefather’ (who represents the spirit of giving and deliberates upon who’s naughty or nice), as well as folk tales of craftsman elves.

But of course, its great similarities to the Saturnalia tradition are evident, stemming from an unknown organic root, which would suggest these traditions have a source very, very far back indeed. Interestingly, the celebration of a Yulefather has a strange similarity to the Saturnalicius princeps custom, the Yulefather representing the spirit of giving (Santa) officiating on the basis of who was naughty or nice, which places the character of Santa Claus in the position of being ‘Saturn for a day’, perhaps. In a realistic or modern sense the parents are the elected princeps or Yulefathers, or perhaps it is the opposite, and it is moreso that the children are Saturn for the day, in role reversal, and are the holiday rulers to be showered with gifts.

The actual date of Jesus’s birth is not known with certainty, though the month of March is commonly suggested. Despite this, in the fourth century AD Pope Julius I (337–352) formalized its date of celebration as December 25th. This was likely done to Christianize the unstoppable party, which had already survived at least one religious conversion, likely a few more. Not surprisingly, like Saturnalia, Christmas during the Middle Ages was a time of charity, rowdiness, drinking, gambling, and overeating. Also the tradition of the Saturnalicius princeps was resurgent: during the medieval period across Western Europe on December 28th, a ‘bishop for a day‘ was elected. Usually this would be a young boy who would issue decrees in the spirit of the princeps. In some parts of France the Saturnalian slave/master reversal tradition lived on in a custom practiced by the priests, who would wear masks or dress in women’s clothing during the boy-bishops reign.

Further examples of this ancestral habit continued into the Renaissance, as many towns in England at Christmastime elected a ‘Lord of Misrule‘, who was the temporary king of the ‘Feast of Fools’. As well as this, another common late medieval tradition was to drop a coin, bean, or other small token into a cake or pudding. Whomever found the treasure would become the ‘King of the Bean’. Amusingly a version of this tradition lives on today, with nobody knowing why in particular they engage in it, or where it originated, as a ghost of the King of Saturnalia and the Lord of Misrule.

Of course some of these fun ancient games were eliminated by the killjoys of the Protestant Reformation, with many medieval customs dying out completely, including gift giving.

The Puritans banned the “Lord of Misrule” in England, with only a mysterious bean or coin hidden in your Christmas pudding remaining as folk-habit. But despite Protestant attempts, in the middle of the Victorian age many of the older ceremonies returned. You might say, once more, that the party could not be suppressed, and undulating organic beast that is ‘the folk’ memoried its habits back into prominence. Thus began again the gift-giving, perhaps the most joyous part of our living celebration. And this joyously still-living custom of gift-giving at Christmastime harkens back to the Roman tradition of giving sigillaria, and the lighting of Advent candles is a direct link from the Saturnalians lighting torches and wax tapers, which themselves harkened to earlier traditions we will never know the details of.

Seneca spoke of the holiday as does any busy Christmas planner prepping their turkey:

“It is now the month of December, when the greatest part of the city is in a bustle. Loose reins are given to public dissipation; everywhere you may hear the sound of great preparations, as if there were some real difference between the days devoted to Saturn and those for transacting business. … Were you here, I would willingly confer with you as to the plan of our conduct; whether we should eve in our usual way, or, to avoid singularity, both take a better supper and throw off the toga.”

Some Romans found it all a bit much. As Pliny laments:

“…especially during the Saturnalia when the rest of the house is noisy with the licence of the holiday and festive cries. This way I don’t hamper the games of my people and they don’t hinder my work or studies.”

This too sounds familiar: the Scrooge, the complainer, for whom the whole event causes stress. A timeless occurrence, apparently.

The great Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry had an allegorical view to Saturnalia and its themes of liberty, cosmology, and birthing the new year.

‘‘For the Romans celebrate their Saturnalia when the Sun is in Capricorn, and during this festivity, slaves wear the shoes of those that are free, and all things are distributed among them in common; the legislator obscurely signifying by this ceremony that through this gate of the heavens, those who are now born slaves will be liberated through the Saturnian festival, and the house attributed to Saturn, i.e., Capricorn, when they live again and return to the fountain of life. Since, however, the path from Capricorn is adapted to ascent, hence the Romans denominate that month in which the Sun, turning from Capricorn to the east, directs his course to the north, Januanus, or January, from janua, a gate.’’

Returning to the prominence of the sun in the holiday was an aspect of the transition to a Christian holiday. Macrobius, also known as Theodosius, lived during the transition of the empire from Roman to Byzantine, and associated the long-standing Capricornian date of the winter solstice as a travelling religious current culminating in solar monotheism. This itself encapsulated the belief that the Sun (Sol Invictus) ultimately encompasses all the varied pagan deities in a monotheistic over-concept, acting as an intermediary faith between the Roman and the Christian, with concepts from both. And indeed we can see early artistic interpretations of Christ as Sol Invictus (as in the mosaic below) as that transition occurred.

The cycle of evolution in culture might be said to somewhat follow this circular trajectory:

ancestral impulse > spirituality > traditions > cultural habits > identity > ancestral impulse.

Let us end with a quick recap of the major traditions shared by the varying incarnations of this celebration, and whatever it might mean that these habits resurface, unconquered, despite their surface meaning being changed or forgotten:

1) An elected overseer, the princeps/yulefather/lord of the bean, who may also represent a Santa Claus figure.

2) There must be a light show over the duration of the holiday, candles or stringed electric lights in our case.

3) The holiday must go for a period of days, at least a week.

4) For some the season is too much and they cry humbug.

5) Decorating trees.

6) Certain plants are sacred to this time, holly, mistletoe, oak.

7) Stockings play a part, from the foot of Saturn himself, or hung over the fire awaiting gifts.

8) Gift giving.

9) Wassailing/caroling, going to strangers doors.

10) Gluttonous feasting and drunkenness.

11) Relaxation of law, business closes.

12) A time of truce and goodwill.

13) Must take place around the dates of the winter solstice and refer to our star: the sun. Which today we may have replaced with the north star.

14) Role reversal, those normally in charge make kings of the lowest.

15) Spirit of charity.

16) Colourful clothing, special hats.

17) The sickled figure of Father Time, (ghost of Christmas future) and unknown alter ego Father Christmas, who was a myth apart from Santa.

The party can’t be stopped.

The Orphic Hymn to Saturn:

Etherial father, mighty Titan, hear,

Great fire of Gods and men, whom all revere:

Endu’d with various council, pure and strong,

To whom perfection and decrease belong.

Consum’d by thee all forms that hourly die,

Cronos as Lord of TimeBy thee restor’d,

their former place supply;

The world immense in everlasting chains,

Strong and ineffable thy pow’r contains

Father of vast eternity, divine,

O mighty Saturn, various speech is thine:

Blossom of earth and of the starry skies,

Husband of Rhea, and Prometheus wife.

Obstetric Nature, venerable root,

From which the various forms of being shoot;

No parts peculiar can thy pow’r enclose,

Diffus’d thro’ all, from which the world arose,

O, best of beings, of a subtle mind,

Propitious hear to holy pray’rs inclin’d;

The sacred rites benevolent attend,

And grant a blameless life, a blessed end.

1 thought on “Christmas: Saturn and Solstice”