Correcting popular misconceptions about Plato (Part Two)

Since 1945, when Popper’s Open Society was first published, Plato’s political theory, as presented in the Republic, has been the subject of criticism from both the left and the right. On one hand, liberals denounce Plato as a proto-fascist; conservatives, on the other hand, accuse him of being a forerunner of communism and feminism. Aside from this last allegation, which will be addressed separately, the grievances of both left and right-leaning intellectuals can be boiled down to a fundamental abhorrence of anything that challenges the two pillars of modern Western society, namely democracy and individualism.

In The Open Society and Its Enemies, philosopher Karl Popper argued that totalitarianism, far from being inventions of the 20th century, has roots in classical antiquity. The emergence of what Popper called the first “open society” in 5th century Athens provoked a reaction from the more ‘conservative’ elements of Athenian society. Plato laid the philosophical groundwork for this reaction, which Popper believed to be underpinned by three main ideas: holism, essentialism and historicism.

Holism is generally defined as the idea that a whole is greater than the sum of its parts, meaning that its parts cannot exist, or be understood, independently of the whole. In the social sciences, “methodological holism”, as Popper called it, is the view that social entities and phenomena cannot be understood by simply analyzing the properties and motivations of the individuals: this is the opposite of methodological individualism. Plato’s holism, Popper argued, led him to adopt the collectivist belief that the needs of the community (or the State) supersede those of individuals and, consequently, the individuals must sacrifice their own self-interests for the common good: “justice, to him, is nothing but the health, unity and stability of the collective body”1.

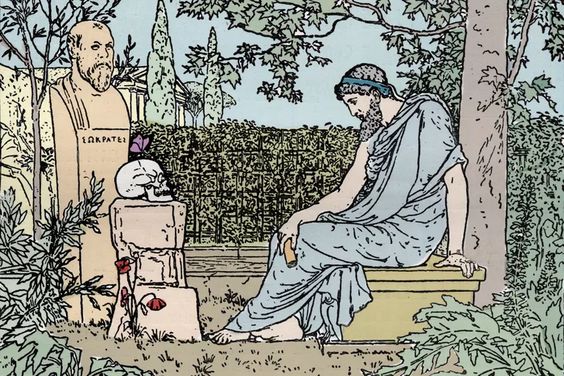

Plato’s defense of the “closed society” was also based on what Popper called “methodological essentialism”: namely, “the view […] that it is the task of pure knowledge or ‘science’ to discover and to describe the true nature of things, i.e. their hidden reality or essence”2. This is the basic assumption of Plato’s theory of Forms. Furthermore, the true, eternal nature of things can only be discovered through intellectual intuition – or, in Platonic terms, through recollection of the Forms –, rather than empirical observation, which can be deceiving. These ideas are fundamentally incompatible with the egalitarian, democratic nature of the “open society”: since true knowledge that transcends sensory perception is not equally shared by all individuals, neither should the responsibilities of government.

Finally, the belief in the existence of eternal, universal principles, unaffected by the cycle of birth and death, engenders what Popper labeled “historicism”, which is to say the view that history is governed by eternal, universal laws and that its future course can be predicted by understanding these laws. Plato adopted a cyclical view of history – already well-established in ancient Greece – and applied the same principles to his political theory: since everything which comes into being is destined to decay, the ideal form of government, which Plato defines as the rule of the philosopher-king(s), will eventually degenerate, giving rise to a series of progressively inferior regimes – namely, timocracy (or military rule), oligarchy (or plutocracy), democracy and tyranny. Thus, Plato sought to devise a system to stave off political and societal decay for as long as possible: the result, according to Popper, is a “closed society” which shares all the features of totalitarianism, such as rigid hierarchy, central planning, censorship and State propaganda.

Despite Popper’s openly declared bias, his analysis of Plato’s political theory is fairly accurate and especially insightful in underlining the inextricable links between Plato’s metaphysics and his practical philosophy. At the core of Plato’s political theory is the ‘City-Soul Analogy’, based on the same macrocosm-microcosm relationship which grounds Plato’s metaphysics. Just as the duty of the rational part of the soul is to rule over the irrational parts, namely the spirited and the appetitive, so too the men in whom the rational part of the soul is most developed (the philosophers) ought to rule over the others (the warriors and the laborers). Likewise, as the parts of the just soul operate in harmony, so do the social classes in the just State, each fulfilling its particular role.

The illiberal and undemocratic nature of Plato’s ideal State is not at all unprecedented in the history of the Greek city-states, where political rights were usually the prerogative of a small minority of the population. What is truly revolutionary is the ascetic, quasi-monastic regime to which the warriors and the rulers are subjected, being forbidden from possessing private property and families of their own, so that they may not be tempted to put personal interests before the good of the whole community. This form of ‘communism’ is, of course, very different from Marxism, both in its ideological foundation and in its application, as it is confined to the ruling class3. The reason is that economic interests, according to Plato, are the main source of discord in society and, since “in every form of government revolution takes its start from the ruling class itself, when dissension arises”4, the ruling class must be protected at all costs from the corrupting power of private property; the members of the working class, on the other hand, can enjoy much greater personal freedom, because their responsibilities – and influence – are infinitely smaller.

1. K.R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, vol. I: The Spell of Plato, London 1945, 106.

2. Ibid., 31.

3. Popper (op. cit., 48) was well aware of this, but the same cannot be said of the armchair critics who talk about Plato’s ‘communism’ without any knowledge of what is actually written in the Republic.

4. Plato, Republic VIII 545d; transl. P. Shorey.