Harmony in Ethics

Ethics: the discipline of determining nothing less than what is good, and what is bad, or the analysis and action of morals upon reality. The word ‘ethics’ derives from the Greek ēthikós, itself derived from the word êthos meaning character (to us ethos suggests ideology).

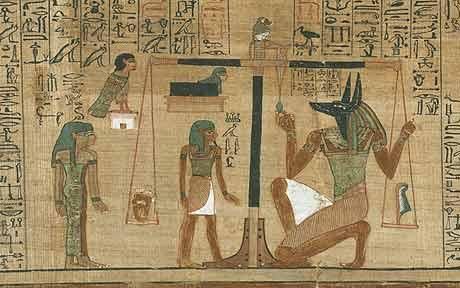

One might say it is the judicial branch of philosophy, or the point at which the philosopher, after establishing whether or not a thing exists, and whether it is good or bad, and whether or not we sufficiently understand it – tries to establish how we should react to it. The road to action is not to be undertaken without establishing the morally best route, and so ethical scale-weighing becomes the penultimate stage of determination, the final self-evaluation before the plunge into action. Invariably in classical thought this discussion leads to the topic of virtue, but virtue alone is only an aspect of the mechanics of ethics.

It is the key to classical thought. Ethics may supersede intuitive nature, and in fact ideally does so, as the higher man makes decisions that defeat instinct (eg. going to the gym vs an instinct to relax). This is the very human energy of willpower and of ethics as a discipline. But what then is the core guiding principle of classical ethical thinking? It is the same core principle found permeating the entirety of classical thinking, it is balance. This might also be understood as: moderation, proportion, and harmony. Harmonia ( Ἁρμονία) is the immortal goddess of harmony and concord.

When the elements of hot and cold, moist and dry, attain the harmonious love of one another and blend in temperance and harmony, they bring to men, animals, and plants health and plenty, and do them no harm

Plato, Symposium, Written 360 B.C., Translated by Benjamin Jowett

This concept of balance, or moderation, was encouraged in all ways, as the extremes led to chaos, and the resulting imbalance a force for immoral degradation. One of his examples was the virtue of courage, being considered the balanced or moderate answer to the polar opposite extremes of cowardice and recklessness. The two extremes are animal responses, the middle road of courage is the balanced higher human response. This balance fulfills the concept of harmony.

The just, then, is a species of the proportionate (proportion being not a property only of the kind of number which consists of abstract units, but of number in general)…

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

As applied to ethics, harmony or balance seems to contain great wisdom, in that the harsh pluralities of right and wrong do not always become clear, when viewed in light of the truly virtuous path, or the path required to reach justice where conflict occurs. It is not equivocal to relativism, which abstractly proposes that all solutions are true at once. The harmonious path seeks ethical answers that determine objective decisions based on virtuous study of both subjectivities (or extremes).

To emulate classical virtue, or practice classical determination, seek balance in your ethics, and your self-judgements. Let reason be the rudder as you pilot a sea of turbulent extremes, for reason moderates passion; and there is no scenario, mild or precarious, for which a carefully measured response or judgement is unwise.

For he who lives as passion directs will not hear argument that dissuades him, nor understand it if he does; and how can we persuade one in such a state to change his ways? And in general passion seems to yield not to argument but to force. The character, then, must somehow be there already with a kinship to virtue, loving what is noble and hating what is base.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics