The Role of Individuality

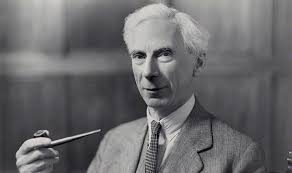

Bertrand Russell, REITH LECTURES 1948

Thanks to Jason Lupus for drawing my attention to this excellent quote from the philosopher Bertrand Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970). It is an insight into the fundamental priorities and structure of work and culture. I would add to his assessment, as I did in my book, that the loss of the trade guilds to corporate money interests in the 19th century were a major influence upon this value change.

– Brendan

In the ages in which there were great poets, there were also large numbers of little poets, and when there were great painters there were large numbers of little painters. The great German composers arose in a milieu where music was valued, and where numbers of lesser men found opportunities.

In those days poetry, painting, and music was a vital part of the daily life of ordinary men, as only sport is now. The great prophets were men who stood out from a host of minor prophets. The inferiority of our age in such respects is an inevitable result of the fact that society is centralized and organized to such a degree that individual initiative is reduced to a minimum.

Where art has flourished in the past it has flourished as rule amongst small communities which had rivals among their neighbors, such as Greek city states, the little principalities of the Italian renaissance, and the petty courts of German eighteenth century- rulers. Each of these rulers had to have his musician, and once in a way he was Johann Sebastian Bach, but even if he was not he was still free to do his best.

There is something about local rivalry that is essential in such matters. It played its part even in building of the cathedrals, because each bishop wished to have a finer cathedral than the neighboring bishop. It would be good thing if cities could develop an artistic pride leading to mutual rivalry, and if each had its own school of music and painting, not without a vigorous contempt for the school of the next city. But such local patriotisms do not readily flourish in a world of empires and free mobility.

A Manchester man does readily feel towards a man from Sheffield an an Athenian towards a Corinthian, or a Florentine towards a Venetian. But in spite of the difficulties, I think that this problem of giving importance to localities will have to be tackled if human life is not to be increasingly drab and monotonous.

In those who might otherwise have worthy ambitions, the effect of centralization is to bring them into competition with too large a number of rivals, and into subjection to an unduly uniform standard of taste. If you wish to be a painter you will not be content to pit yourself against men with similar desires in your own town; you will go to some school of painting in a metropolis where you probably conclude that you are mediocre, and having coming to this conclusion you may be so discouraged that you are tempted to throw away your paint brushs and to take money-making or to drink, for a certain degree of self – confidence is essential to achievement.

In renaissance Italy you might have hoped to be the best painter in Siena, and this position would have been quite sufficiently honorable. But you would not now be content to acquire all your training in one small town and pit yourself against your neighbors. We know too much and feel too little. At least we feel too little of those creative emotions from which a good life springs.

In regard to what is important we are passive; where we are active it is over trivialities. If life is to be saved from boredom relieved only from by disaster, means must be found of restoring individual initiative, not only in things that are trivial, but in the things that really matter.

Bertrand Russell