Against Escapism

By Peteseph of TOTHO.

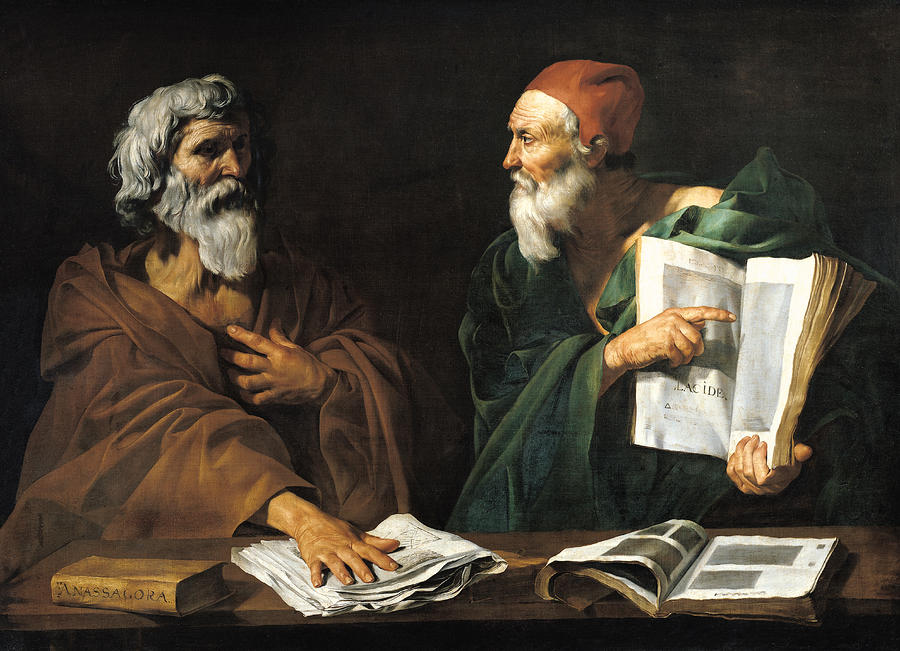

Aristotle rightly said that we work in order to enjoy leisure. That is, we work to live; we don’t live to work. The Greek word for leisure is skole, from which we get the word school: Our leisure is meant to be directed toward higher things like study and being a student of life, observing its Beauty and taking note.Too often, we find ourselves spending our leisure doing something unfulfilling, meaningless, the opposite of joy-bringing; we fritter our time away on inane diversions instead of enjoying the Beauty, Wonder, and Goodness of life. Why? Out of habit.

The Greeks, foremost among them the Pythagoreans, stressed the importance of cultivating good habits. Our habits shape us into who we are, and it is simply by the habit of virtue that we become outstanding individuals.The problem with spending leisure on diversions (or turning away from life), that which we call escapism, is that it views life as a negative thing: It follows from a mindset that sees the negative things happening in one’s life and conflates these negative occurrences with life itself, falsely attributing negativity to all. There can be no greater error than to see life as anything other than Good. Then the beleaguered soul seeks to escape life and spirals into unfulfilling attachments, passions, and addictions. Nothing brings this soul happiness, no matter how desperately it seeks happiness and deludes itself that the fleeting pleasure the attachments bring is happiness itself. For, indeed, one who seeks happiness will necessarily be unhappy; happiness happens as a result of abiding in the Good, of Love, of Order (Ma’at).

What the escapist soul fails to understand is that the negative instantiations posed toward an individual are simply part of life, and that life is Good and always is. To see things in the bigger picture, the negative instances we deal with in life are actually a positive thing, opportunities for us to develop, exercise and maintain our virtue. Opportunities for us to love, to flow with the Way, to enact the ritual of joy, to abide in the Good, a necessary part of the sublunary (generative) realm. The escapist soul must come to learn that the Good is the root of all Being, and that the universal Good is our truest self, not our individual self. Thus, the soul will not be troubled by individual life events but will rest in the understanding that his true Self is the eternal Good, which may never be diminished.

The soul must make peace with life and be content with life as it is, or else it will never be happy.

Do not fall into the mindset that you do not want to do the things you have to do; rather, see them as things that you get to do. For, if we don’t make peace with the things we have to do, then we will not make peace with life, and if we do not accept life, do not make peace with it, do not content ourselves with it, then we will never be happy. If you content yourself with the simplicity of life, then you will never be disappointed. As the Tao Teh Ching says: “The Tao is like water: It is tasteless and abides in places that man hates.” Therefore, do what you should being doing, and you will find that there is nothing else that will make you as happy as that. And when you rest, you will rest restfully, and not worry that you should be doing something else. Indeed, there is a time for rest, a time of yin.

Do not defer what you should do, and do not delude yourself that escapism is rest; escapism will become a habit and will damage your health, spirit, and enjoyment of life. Devote your leisure to healthy, restful, non-escapist activities like reading, taking a walk or exercising (especially in nature), writing, prayer and meditation, music, spending time with family, cooking, crafting, etc., and make these activities your habits. This is the way to become excellent and sharpen your taste, or gusto, of life. Leisure works much like a Chinese finger trap: Try to seize happiness, and it evades you; pursue leisure for the sake of benefit, and it doesn’t provide leisure or rest.

Use your leisure today to read “The Continuity of the Parks” by Julio Cortazar. It is a very short interesting read about escapism coming back on us to cause our demise. Do not fail to get out and enjoy nature: Take a walk out there, sit out there, meditate, play an instrument, write poetry or contemplations, be at peace in the Beautiful, spend time with your loved ones.

In his Leisure the Basis of Culture, Dr. Josef Pieper points out that leisure “is not possible unless it has a durable and consequently living link with the cultus, with divine worship” (xix; New York: Pantheon Books, Inc., 1952). Just as leisure depends on cultus, “culture depends for its very existence on leisure” (ibid.), and thus it is in leisure that we have the link between culture and cultus. Herein is seen a sense of the importance and true nature of leisure. Peiper says of leisure that it “is not a Sunday afternoon idyll, but the preserve of freedom, of education and culture, and of that undiminished humanity which views the world as a whole” (33). Leisure, he also says, must necessarily occur for its own sake, not for some utilitarian end; this is to say that the re-centering act occurs as a surrender to the animating Good within oneself, to return to one’s heart and have faith and know that All is Good, to listen in reverent silence. He likens this act to that of prayer or sleep: The beneficial effects of prayer or meditation must not be a consideration when undertaking these tasks, or else the task will not be able to occur and the effects will not be gained; and regarding sleep, one cannot will oneself to sleep and rest but must rather give oneself to it.

On reverent silence, in addition to being highly esteemed by the Pythagoreans and future ascetic traditions as an exercise of humbly listening for God rather than the assertion of oneself, the poet Lord Byron said that there are two types of people in the world, the bores and the bored. The bores being enchanted by the most ordinary things of life like a tree (content with life and understanding it as Wonderful, the silent and reverent contemplation of which we are speaking) and the bored, who are attached to the ego and seek constant novelty and base gratification, which is only ever unfulfilling. The bores are the wise immortals and happy-hearted, as the Tao Teh Ching says that the key to eternity is in the everyday and that herein lies contentment. The godless bored see a cat and think “it’s just a cat,” while the bores see a cat and behold it with wonder and see its unique personality, naming it, enjoying it, and seeing how it is animated by and returns to the Divine Good (the Way). Part of the problem with the bored, ego-minded, irreverent person is that they value work and rational knowledge too much, overlooking the importance of leisure and its contemplative, intuitive knowledge. As a consequence of ego-attachment, boredom arises out of spiritual despair, emptiness, and sloth, which the ascetic contemplative tradition calls acedia. This is a refusal to assent to the highest Good, i.e., to realize our Divine nature in love — to enjoy something (concupiscent love) and will it the good for its own sake (benevolent love) — a spiritual inertia, a total lack of seeking for higher Goods than the comforts and ego-affirmations of life, refused through cowardice from greater exigencies and discipline.

Such a spiritually bankrupt soul, who does not look to the well of Wisdom that is the transcendental principles of Being — to Truth, Goodness, and Beauty — and uses their leisure improperly and ineffectively, feeling restless and idle and engaging in activities like games and shows which lack the celebratory, festal, and spiritual nature of free contemplative leisure.They remain restless because the demands of the workforce (of the social functionary) are the only god to which they assent—and only this by immediately inevitable necessity. Such is the fault with seeking to be useful and rational (servile work) as opposed to embracing the non-utilitarian pursuit of contemplation of the sacredness of one’s Being and world (liberal arts), which is in fact the religious foundation without which society cannot exist.

In this, we can see why Confucius esteemed Ritual as the heart of Culture and the fabric (Way) of society, and it is in this sense that the Taoist texts stress the elusiveness of the Way, the usefulness of a vessel lying in its emptiness. Or the importance of wu-wei, or doing nothing (efficacious non-action), such as in the Chuang-Tzu where we see numerous examples of this, such as the monkey who shows off his skill being shot down by hunters, the useless gnarly tree being spared from being felled like the useful straight trees, and the drunk passenger who falls out of the wagon and is unharmed because he does not do anything to resist the fall but rather goes along with it. Indeed, Chuang-Tzu talks about the absolute necessity of the useless, likening it to the ground that we are currently standing upon: without it, how long could we stand where we currently do?

It is by setting aside a time for pursuits that have no immediate use but are nonetheless fruitful and life-giving that man finds himself. For, leisure allows man to be who he really is, to realize and actualize his nature as the Good ensouled, and this looking to God, who is the spirit of life, is the very source and meaning of inspiration. Similarly, we set aside non-utilitarian space for the cultus, upon which leisure depends, to create the temple. And ritual re-awakens us and shows us the Good within ourselves and the world, and sacrament is a visible sign of assent to and pursuit of this Good, which is the communal actualization (completion) of the contemplative process.

Pieper writes, “Separated from the sphere of divine worship, of the cult of the divine, and from the power it radiates, leisure is as impossible as the celebration of a feast. Cut off from the worship of the divine, leisure becomes laziness and work inhuman…. The celebration of divine worship, then, is the deepest of the springs by which leisure is fed and continues to be vital” (48-49).

One final note to make about leisure is that it may be realized through the four divine madnesses of which Plato writes in his dialogue, Phaedrus. Plato writes that the divine madnesses are noetic (intuitive) exercises by which we perceive and understand the divine reality of the Good immediately, intuitively, and holistically, in the same way that, as Pieper puts it, “our eye apprehends light or our ear, sound” (12). The divine madnesses allow us to observe the principles embodied by certain gods to bring us to the highest divine Good; the divine madnesses are activities through which limited reason (dianoesis) is transcended and we behold the magnificence of the Good that animates us. Such happens in the divine madnesses of music and prophetic poetry, when the improvisational artist gives themselves to the art and moves where their heart takes them. The other madnesses are erotic love (sometimes associated with contemplative philosophy) and ritual, or action that affirms the Good. In the same way the lover makes love passionately and without calculation, so too does the lover of the divine devote himself and praise and adore the living, spiritual Powers, or gods, which are more real than this impermanent material world.

Plato says “But the Gods, taking pity on mankind, born to work, laid down the succession of recurring Feasts to restore them from their fatigue, and gave them the Muses, and Apollo their leader, and Dionysus, as companions in their Feasts, so that nourishing themselves in festive companionship with the Gods, they should again stand upright and erect.” This quote also shows how the commoners of the medieval era and antiquity worked about half as much as us moderns (having They many days off due to feast days and festivals to the gods, or feriae) yet still enjoyed plenty of wealth, despite lacking the technological efficiency we possess (it should be obvious that the money masters rig our system to keep us slaving in squalor and racial-spiritual destitution). Through contemplation, the re-centering and channeling practices of the divine madnesses, and through participating in culture, true leisure is realized.

Abide in the Eternal Good.

→Temple of The Hermetic One on facebook