La Folia de España

By Lucca Zimerer (translated by Victoria)

“Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything” – Plato.

With its origins in the Iberian Peninsula as a fertility dance, the Folia — known in French as Folie — became popular in the compositions of musicians such as Arcangelo Corelli and Sergei Rachmaninoff during the Baroque and Romantic periods. However very little is said about these songs: do they really have their origins in Spain? Who started the trend of composing folies? What makes them both so simple and so complex?

Truly Spanish origins?

While the name affirms that the theme comes from Spain, it is not Spanish, but actually Portuguese. The dance, well known in Portugal, was exported to castellan lands, and from there became popularized around Europe. Lorenzo Franciosini Florentino, in his “Vocabulario Español”, defines a Folia as a “well-known Portuguese tune which is played in the guitar” (un suono Portughese assai noto, chi si suona con chitarra). In other sources, such as in the “Neuman and Baretti’s Dictionary of the Spanish and English Languages”, by M. Seone, the Folia is defined as “a kind of merry Portuguese and Spanish dance with castanets”. In his book “De musica libri septem”, Francisco de Salina describes the Folia as a lusitanian dance and, besides that, the first reference to such dance occurs in the works of Gil Vicente, a portuguese dramaturgist, in his “Auto da Sibila Cassandra”.

After this popularization in the Iberian Peninsula, the theme expanded itself throughout the 1600s and 1700s to Italy and France, where it had its apogee as a courtesan and aristocratic dance. It was beloved by the nobles, even though it was not performed by them, but by professionals, in virtue of the choreographic complexity. Through this proliferation and popularity it culminated in directly influencing more than 150 composers until the 1900s.

Early and Later Folia

However, even though the Folia originated in iberian dances, the music played in these circles was a little bit different than the ones later composed by various musicians. The early folia consisted in fertility dances, where the dancers carried on their shoulders men dressed as women, while induced to frenetic states of conscience by the musicsal rhythm. The later folia, on the other hand, was somewhat different: a simple melody of sixteen bars with a standard chord progression, established by the composer Jean-Baptiste Lully.

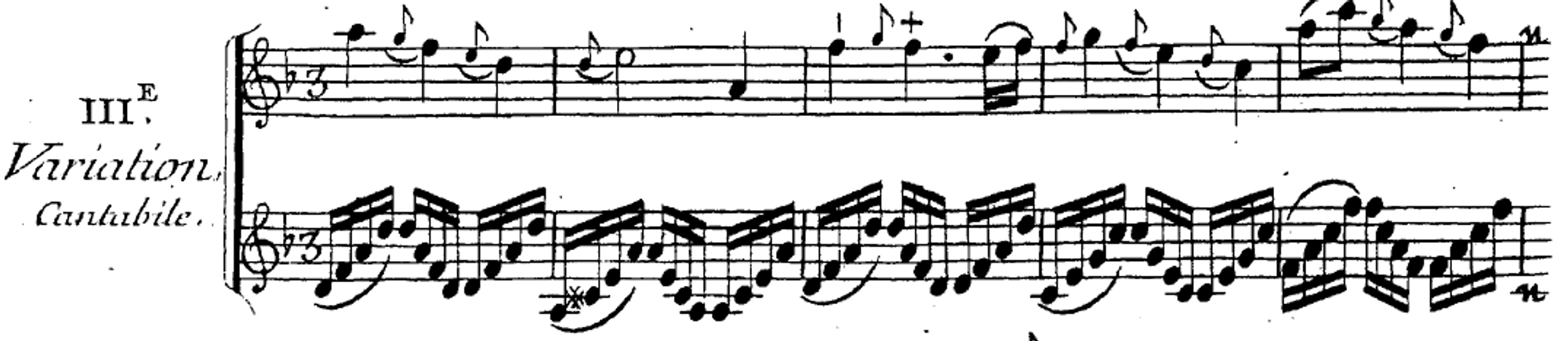

But, if the Folia is just a simple melody and “fixed”, how can it be a theme so extensively used throughout the centuries? The answer is in the variations. The pieces never follow the melody demonstrated by Lully, but variations on it, while obeying the chord progression. Take for example the Folie d’Espagne, by Guignon:

The beauty of the song is at the ornamentation, the variations — in creating and improvising new techniques and sounds over a predetermined pattern; so open it is to variations that not only it is possible to write a piece with a few quantity of these for an organ, but 24 for a full symphonic orchestra, as did Salieri. In fact, it is possible to talk about of an “eternal recurrence” of the Folia da España, for it is the most occurring theme in musical history.

Folly in post-Renaissance arts

Still, it is not enough to say that the Folia achieved fame for it’s capacity for improvisation and creativity which it granted the artists. No, it is necessary to go beyond, search for more profound reasons. The subject of Frenzy, of folly, of madness and melancholy was very present in the artistic thought of Antiquity, such as in the works of Homer, where Ajax, possessed by frenzy, massacres all the camp’s cattle, or Seneca’s Hercules furens. Plato affirms in his Ion that the poets are possessed by a divine madness, and classical medicine asserts that melancholics, in virtue of the high quantity of black bile, are more probable to reach madness — it is not for other motives that intellectuals were traditionally considered to have a spark of the mad. This idea that folly was something exalted would be present on the mysticism of Platonic tradition during the Renaissance, as it is seen in the works of Marsilio Ficino, specifically in his De Vida Libri Tres, where it is said that intellectuals and artists are closer to insanity, and so to melancholy, and it is through melancholy that Platonic Love was reached. The theme of madness was very present during and after this epoch: just see Eramus’ of Rotterdam Moriae Encomium.

Maybe it is possible then that the Folias are not only a musical theme, but the subject of madness itself. Popularized in an aristocratic ambient, where rationality was praised, the simple idea of folly — a Folia — in it would represent not only musical innovation, but also insanity and frenzy guided by reason, where a song of wild character would present itself as tamed, transformed in something solemn and harmless. Something elegant, something French — melancholy, that which endows human beings with intelligence and rationality, giving birth and controlling the Furiae.

Conclusion

It is possible to say so that the Folia is not only a song, but a whole subject with a more profound significance. Besides the great compositions that were derived by the common motif, it carries a message, a true éloge de la folie, that represents a trait of the cultura and, in a sense, spirituality that presented itself in the Renaissance and reverberated throughout the centuries. The Folia is a mirror of the praise of Folly of its time.

Lucca Zimerer on twitter: @zimerer