Pagan-Christian not Judeo-Christian

Uncovering the pagan foundations of Christian doctrine1. Part One.

By: Aglaophamos

Most people are aware that many Christian festivals – such as Christmas, Easter and All Saints’ Eve – incorporate elements of ancient pagan traditions, but very few know of the pagan origins of the core doctrines and beliefs of the Christian religion. This is understandable, as the history of religions is not a popular topic of interest outside of academia and, even among academic circles, the claims of exclusivity put forth by the Christian Church have largely suppressed the discussion of the pagan roots of Christianity. Nevertheless, I am convinced that all people of European descent stand to benefit from learning about the history of Western religion: on one hand, Christians will hopefully gain new appreciation for their own pagan heritage and, on the other hand, Neopagans and non-religious people will cease to regard Christianity as being completely foreign to them.

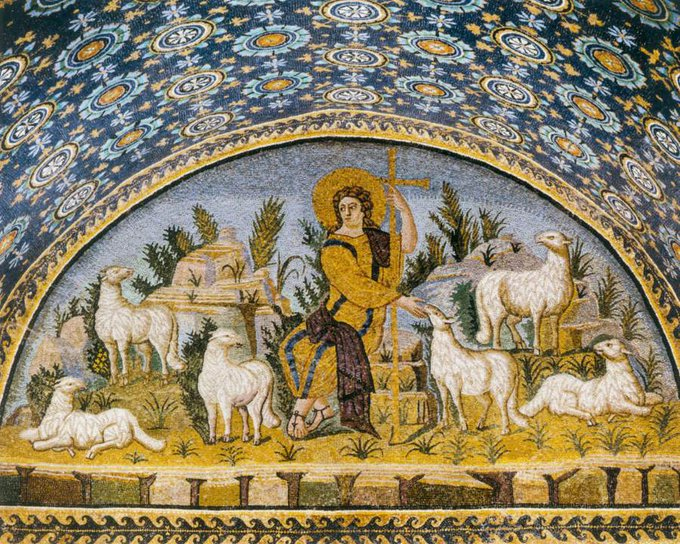

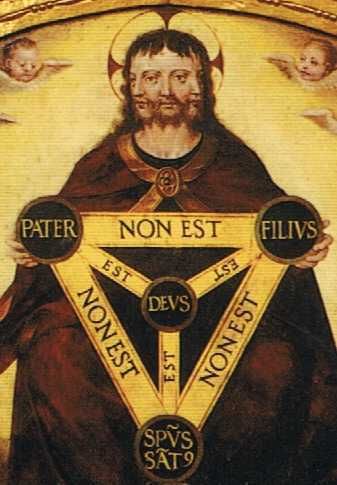

Let us start, then, by looking at the doctrine of the Trinity, which states that God is one, but at the same time exists as three consubstantial persons – the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Although the triadic nature of God is already referenced in the New Testament2, Trinitarianism was codified as a coherent doctrine only towards the end of the 4th century, with the Council of Constantinople (381) officially instating it as dogma. Among the foremost contributors to the development of the trinitarian doctrine was a Christian Neoplatonist named Origen (c. 184 – c. 253): he was a student of Ammonius Saccas, the founder of Neoplatonism, at the Academy of Alexandria and later went on to found his own school in the city of Caesarea (Palestine). Origen used the teachings of Plato and the middle Platonists to interpret the Christian scriptures and applied the tripartite model of a Supreme One – or Good –, a secondary Eidetic (that is to say, pertaining to the world of Forms) Being correlated with Eidetic Knowledge and a tertiary (World-)Soul to the God of the New Testament: he was the first Christian theologian to speak of Father, Son – or Logos – and Holy Spirit as three distinct ‘hypostases’, a term which is still used today to denote the three persons of the Trinity. The doctrine of the Three Primal Hypostases was developed by Origen from passages of Plato’s Timaeus, as well as from Ammonius’s lessons at the Academy, and was further perfected by another of Ammonius’s disciples, the Neoplatonist Plotinus (204 – 270)3.

The concept of ‘Logos’ was also adopted by Christian theologians from Greek philosophy. Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD), a Jewish Platonist who sought to harmonize Jewish scripture with Greek philosophy and whose work heavily influenced early Christology, identified Plato’s Forms with the Creator’s thoughts and the Logos – that is, the totality of these thoughts – with God’s creative principle, the organizing principle of matter; thus, Philo defined the Logos as God’s first-born, the means through which God acts on the material world. John the Evangelist and other New Testament writers4, influenced by Philo’s exegesis, identified the divine Logos with Christ and early Christian theologians, such as Justin Martyr, Origen and Clement of Alexandria, further developed Philo’s Logos doctrine by adapting it to the Christian faith.

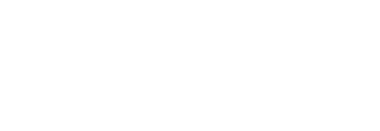

Eschatology is another area in which the influence of Greek religion and philosophy – specifically Platonism – is especially apparent. The belief in the immortality of the soul and in post-mortem punishments and rewards, unknown to ancient Judaism, was adopted by Christianity from Greek mystery religion. The most popular of the ancient Greek mystery cults, attested as early as the 5th century BC and spread all over Greece, Asia Minor and Southern Italy by wandering priests, were the Orphic-Bacchic mysteries, which promised an afterlife of eternal bliss to all initiates; the uninitiated, on the other hand, would have to carry water in broken pitchers or lie in the mire as punishment for failing to purify their souls. The initiation process usually included some form of fasting, bathing or washing and, finally, a communal meal and ritual wine drinking: all of these customs were adopted by the early Christians and are still practiced today, albeit in a slightly different manner5.

The doctrine of original sin also had a precedent in the Orphic mysteries. According to the cardinal myth of Orphism, the infant Dionysus, son of Zeus and Persephone, was violently murdered by the Titans, who tore him to pieces and feasted on his flesh – only the heart was saved and from his heart Dionysus was born again; Zeus exacted revenge on the Titans by incinerating them with his thunderbolts and from their ashes mankind was born6. As punishment for the crime committed by their divine ancestors, humans have to endure an infinite cycle of reincarnations: freedom from the prison of the body is only granted by Dionysus – or his mother Persephone, as was the case with the Eleusinian mysteries – to those who, having duly purified themselves, have been initiated into the mysteries. Since the concept of primeval sin is foreign to Judaism, early Christianity must have derived it from Hellenistic thought – either directly from the Orphic-Bacchic mysteries or, more likely, through the influence of (Neo-)Platonic philosophy. Indeed, such concept was first introduced in the context of Christian theology by Paul the Apostle (d. c. 65), who is generally regarded as being responsible for turning Christianity from a Jewish cult into an independent religion catering to a predominantly Greek and Roman (i.e. non-Jewish) audience7.

End of Part One.

1. I use the terms ‘pagan’ and ‘paganism’ to refer to the whole of pre-Christian or non-Christian Aryan – i.e. (Proto-) Indo-European – religious beliefs and traditions.

2. Cf. e.g. Matthew 28:19, 2 Corinthians 13:14, 1 Peter 1:2.

3. Plotinus’s teachings are known to us through the work of his student Porphyry (c. 234 – c. 305), who compiled and edited his writings into a series of fifty-four treatises organized in groups of nine, hence the title Enneads, from the Greek enneás, ‘body of nine’.

4. Cf. e.g. Hebrews 1:1-3, John 1:14.

5. Water baptism is practiced by nearly all Christian denominations and so is the Holy Communion, where sacramental bread and wine are consumed after being consacrated by the priest. In addition, Catholics dip their fingers in holy water when entering the church and fast for at least one hour before receiving Communion.

6. The fact that the first complete account of the myth is related by the Neoplatonist Olympiodorus (495 – 570) has led some scholars to question its antiquity, despite the many hints found in pre-Hellenistic texts; in reality, the lack of explicit references in more ancient sources is due to the religious taboo which forbade initiates from divulging the story of Dionysus’s death.

7. Cf. Romans 5:12 «Wherefore as by one man (scil. Adam) sin entered into the world and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned. By one man’s disobedience many were made sinners».