The Return of Becoming

Goethian life-image and the next Sturm und Drang movement

As denizens of the postmodern West, we have all been raised in a culture centered around systems. Economy, politics, the universe, even Life itself, are all primarily understood in terms of their individual parts. The esteemed logician of any field pays little mind to what the whole presents itself as, seeing it as a mere mask concealing the Truth waiting to be uncovered by the lens of reductionism. The formal application of this idea can be traced back to the atomism of Newton, who interpreted the universe on the basis of corpuscular heterogeneity, but it quickly spread to biology via Darwin, the father of modern biology in the eyes of the academic establishment. I am here to tell you that this fetishization of systems is a cult of the Dead that has gotten Life, and perhaps Creation as a whole, fundamentally wrong from the start.

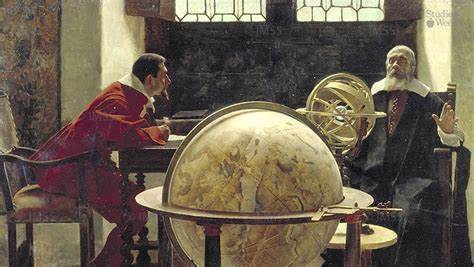

In the heyday of Newton, as the Enlightenment spirit began to claim its final victory within the minds and hearts of Western man, one of the staunchest bulwarks of resistance was that of German romanticism, largely headed by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. What I am most concerned with detailing here is his theory on -Life-, and how the organic differs from the inorganic in ways that the science of his day had begun to perilously overlook.

For both Goethe and the reductionists, the inorganic can be perfectly symbolized with a Newton’s cradle. One ball swings to strike the one next to it, and that ball is in turn sent in a certain direction at a certain velocity relative to that of the first ball, and so on throughout the rest of the system. When one views this phenomenon from the outside, he can comprehend it purely from the sense-perceptible qualities at work in each ball as it acts upon the other. The factors of mass, direction, and velocity can be measured in the first ball and used to predict the same in the second, and from this process of reasoning we can glean the entire conceptual framework of the phenomenon as a whole.

Both the material phenomenon that we observe and the concepts we derive from it coincide. Nothing exists in former that does not exist in the latter, and vice versa. Therefore when comprehending any inorganic phenomenon, nothing immaterial, nothing outside of the senses, needs to be taken into consideration to get the full picture. To paraphrase Rudolph Steiner, inorganic nature can be completely explained out of itself, without any need to go outside of or beyond it.

With the organic, however, the sense-perceptible factors of each part or organ (such as form, color, size and function) cease to be determined by the same criteria. The size or form of a plant’s root do not directly determine that of the leaf. The phenomenon can no longer be comprehended as a machine guided by a domino effect of tangible events. In the organism, the sense-perceptible qualities now arise from a unity that is not sense-perceptible. The beating of my heart, breathing of my lungs, and movement of my legs do not mutually direct one another, but are rather directed by something that both permeates and hovers above them. As a result, the introduction of Life seems to be an intrusion of the laws of Nature themselves, breaking rules that were previously universal.

Science had always acknowledged this distinction but had, even as late as Kant, concluded that the result was an impassable chasm of knowledge separating the inorganic and organic. Only the former, by virtue of being explainable out of itself, was capable of being known by Man, while the latter would remain an enigma. One could intellectually recognize the existence of the organic unity, but not understand its inner workings. Goethe was the first to reject this, and asserted that it is fully possible to understand Life, given that one is willing to forfeit discursive thinking in favor of a more intuitive approach.

In light of this inherent, intangible unity to the organic, one of Goethe’s foundational principles was that Life is exactly what it presents itself to be. The only way for one to comprehend the unity above the parts is to view an organism using one’s intuition, visualizing its Nature abstractly. To solely use logical observations rooted in material phenomena would sap all life from the conception. One would no longer be studying a living organism, but a corpse. To translate this into a modern practical sense, think of how contemporary biology primarily studies and understands organisms based on dissection. How could one do so, knowing that the only way to properly dissect requires the organism to have first expired, and claim to understand how Life works?

Every insight gained from such study is based on an object that has Become, and settled into a static state devoid of self-initiated change. True Life, on the other hand, is in a perpetual state of Becoming. Muscles grow or atrophy. Cells die and are given fresh replacements. Food is consumed and digested. All toward the ends of a purpose tailored for the entire organism, the pursuit of which will only end with death. To pierce the veil enshrouding this purpose, one would have to observe the organism at the height of its powers, in its natural state, doing what it is naturally driven to do by its own Will.

Using this method of inquiry Goethe realized that the organic world eternally moves through alternating phases of contraction and expansion, which we will refer to as systolic and diastolic respectively. Thus the entire force of Life’s development is captured in the beating of a heart or the process of breathing, and can be applied to every level. Organic forces concentrate themselves, strive to unify, but will eventually reverse the process and seek solitude, individuality, distance between one another. This principle was illustrated by Goethe both in his science and his poetry.

In the realm of botany, Goethe demonstrated that if one traces the stages of growth in a plant, one first arrives at the seed. The plant at this stage is in a state of maximum contraction, the entirety of its Being condensed to a single point. This is followed by an unfolding as the plant spreads itself out during the formation of leaves. One will notice that the leaves at the bottom of a plant are typically more compact, while the top leaves are more ribbed and spread out. Out of the leaf forms the bud, yet another contracted manifestation of the plant, which again gives way to expansion in the form of the flower, which is even more delicate than the leaf. The alternation of systolic and diastolic, the beating of the archetypal Heart, is intuitively grasped from a single plant’s journey from seed, to leaf, to bud, and finally to flower.

In Goethe’s poetry, the most striking example would be the duality of his two poems Ganymed and Prometheus. The former gives voice to Ganymed, the youth who in Greek myth was seduced and taken up by Zeus as his lover. It is meant to depict an ecstatic union between Man and God, a divine unity of existence. On the other end, Prometheus contains a bitter diatribe by the titular character against Zeus, portraying Man as rival creator to the Gods seeking to create his own world free of demiurgic tyranny. In these two poems we see a tension of opposites, unitive religious fervor vs vitriolic individual will. Goethe believed that both were integral halves to the human condition, an ideal in stark contrast to the dualism one sees today between the likes of the Christians and atheists.

Much more can be said on these topics, but my goal is to merely overview how Goethe’s view of Life differs from that of the reductionist’s of today’s scientific era. Reason, as Spengler would put it, kills as it cognizes. It separates what was meant to be whole into disparate parts, and thus loses the very essence that created these parts to begin with. From a Goethian viewpoint, this is the source of the great rift in understanding that has prevented science from gaining any significant ground in the understanding of Life, the world, or even the universe as a whole during our epoch.

We now zoom out to Sturm und Drang, the greater cultural movement surrounding ( and largely spearheaded by) Goethe’s work. In this eruption of romantic vitalism, rising from Man’s instinctive revolt at the sight of the Enlightenment’s cult of dissection, we see much of what is needed and indeed already occurring in our own era. The movement, translated as Storm and Stress, asserted that Life was only comprehendible through intense passion or struggle, as opposed to the cold, detached rational analysis of the day. Works like The Sorrows of Young Werther depicted universal themes from the viewpoint of a protagonist driven and often beset by the tides of deeper emotional forces. To the romantic these forces were the true locus of movement to which the more concrete and conscious factors like reason were subservient.

Nietzsche himself was a Sturm und Drang compressed into an individual. The Western world was still asleep, languishing in dreams of rationalist utopia. He was one of the first of the restless, those jolted awake in the middle of the night and fated to behold the horrors inhabiting the waking world alone. He was a Romantic born in the twilight of the regime of Systems, and thus within him was the seed of a new vitalist uprising. We have seen further expansions upon his work in the likes of Evola and Jünger, which has blossomed even more recently in the dissident vitalism of Bronze Age Pervert. This serves to demonstrate that the greater organism of Man is returning to his roots, his spiritual home.

What is left to us now is to continue on this path, to further exalt the individual over the collective, struggle over comfort, passion over logic. On an individual level we must learn to crave challenge in all areas, be it physical, intellectual or spiritual. On the physical level this comes from fitness, health, athletic competition, pursuing danger and depriving oneself of unnecessary comforts. Intellectually we must plumb the minds of the great thinkers before us and turn the energies housed within towards our purposes. We cannot merely cast out Reason, fleeing the city within us back to the wildlands of primitivity. Instead we must subjugate Reason through sheer force of -Will-, and restore it back to its place as a servant of Passion.

In the realm of spirituality, no longer can we afford to fear and demonize the likes of aggression, chaos, anger, war and even madness. For too long Western man has turned away in fear from the primordial forces welling up deep inside him, seeing them as an inner monster threatening to consume his “real self” comprised of morality, reason and love of safety. It is for this reason that the modern New Age trend is a dead end, a mere reassembly of the same entropy it masquerades as a reactionary movement to. Though it does look down upon dogma and assert helpful things such as meditation, individual thinking and belief in the power of one’s own mind, its morality centers around fantastical ideas of man “evolving” into even greater layers of morality. Its prescription for the modern decay is not enough compassion or peace, when the exact opposite is the case. These people believe that Man will eventually evolve past the need for war, division and force into some sort of Brahmin master race where all are equal in an eternal unity. This at best an infantile delusion and at worst the final play of the Leviathan itself, threatening to snuff out the flames of Man’s soul forever.

The first Sturm und Drang was tragically destined to fail at stopping the Enlightenment from tightening its grip on the West, playing the role of the warrior who falls to the dragon despite wounding it in a hard battle. At that point the culture had made up its mind, and even the most noble reactionary movements rarely succeed in stemming such a tide. Now, however, the dragon has grown old. Bloated from the spoils of its hoard. Its raging fires reduced to smoldering embers. The time has come for the spirit of the warrior to rise again and finish what his ancestors started, establishing a cultural worldview that sees creation itself as a mighty organism. I have been dedicated to this cause as long as I can remember, even before I was able to formally express it, and I will see it through to the end no matter the cost.